Details

Construction

Dimensions

History

Experimental submarines were chronicled from the mid 16th century, but most notable were the Americans David Bushnell and Robert Fulton in the later 18th century. Fulton sought to persuade Napoleon that the French answer to British naval mastery might lie in a fleet of submarines. He was assisted in the production of a prototype, the NAUTILUS, which enjoyed modest success but failed to impress the French naval ministry. Undaunted, Fulton went on to demonstrate his principle to the British, but the Lords of the Admiralty also failed to grasp the possibilities. Credit for the prototype of a viable submarine belongs to John Philip Holland whose pioneering attempts at submersible vehicles were sponsored by the Fenian Brotherhood. His career as a submarine designer began properly in 1888 when he won a US Navy design competition, although no subsequent building contract was placed. In 1896, he was successful in another contest and formed the Holland Motor Torpedo Boat Company, which grew into the Electric Boat Company, still the principal builder of submarines in the United States.

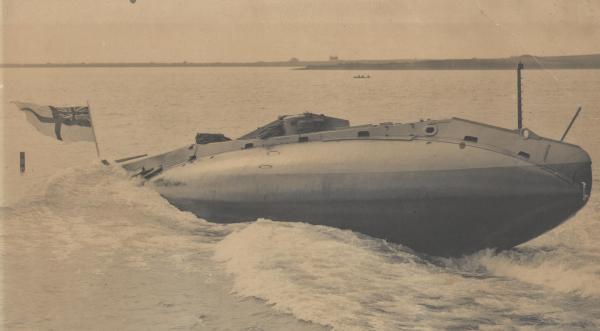

In 1898, his latest experimental craft, HOLLAND TYPE VI, underwent successful trials in New York harbour and was acquired by the US Navy in April 1900, becoming USS HOLLAND, the first submarine in the US Navy. The Royal Navy was cautious in its approach to submarines, supposedly because it was said to be “underhand, unfair and damned un-English”. But, with the introduction simultaneously of several successful designs, most notably USS HOLLAND, the situation began to change. The 1900-1901 Naval Estimates included a surreptitious order for five of the American vessels, at a total cost of some £175,000. Drawings and components were supplied for an improved design, slightly bigger and more powerful than USS HOLLAND and, on 2 October 1901, Britain’s first submarine, HOLLAND I, was launched without ceremony, since she was technically an experimental craft. Her petrol engine gave a surface speed of 8.5 knots (speed submerged, 7 knots), and she had a surface endurance of 500 miles at 7 knots. She carried a crew of nine men.

In September 1902, the First Submarine Flotilla consisting of the first two Holland boats with the gunboat HMS HAZARD serving as depot ship arrived in Portsmouth under the command of Captain Reginald Bacon RN. Development from then onwards was rapid and soon influential figures in the government and the Service began to see the potential of submarines. The development of the marine diesel engine and many other technical innovations which enhanced the sea-going capabilities of the newer boats also opened up their possibilities for offensive use, which fitted neatly into Admiral Fisher’s evolving concepts of sea warfare. By this time, the pioneering HOLLAND I and her sister boats had become obsolete. Whilst under tow on route to the breaker’s yard, on 5 November 1913, near to the Eddystone light she was lost, happily without casualties.

In 1980, the first steps were taken to locate her remains and, on 14 April 1981, a naval diving team identified the wreck, “confirmed as a submarine of correct dimensions for HOLLAND Class”. The following year she was recovered and taken to the RN Submarine Museum where, after extensive cleaning and treatment with anti-corrosion chemical applications, in 1983 she was placed on display. By 1993, the still chloride-infested hull showed signs of extreme deterioration. A sophisticated scientific conservation process was initiated. The first phase was remedial intervention which involved soaking the submarine in a passive electrolytic solution - requiring the construction of a tank to enclose the submarine, holding some 800,000 litres of sodium carbonate - in order to facilitate the removal of the chloride ions. This tank had to be drained and re-filled three times with a fresh solution of sodium carbonate to maximise the amount of chloride being removed. Finally, in December 1998, the tank was emptied for the last time and tests showed that the levels of chloride were now in balance. The second phase of the conservation process was preventative, through the construction of a specially designed, de-humidified gallery to permanently house the vessel in a controlled environment of less than 40% R/h.

The new HOLLAND gallery at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum was opened on 17 May 2001, by the Countess Mountbatten, during the Centenary Year of the Submarine Service. There, with HMS ALLIANCE, she forms part of a permanent memorial to the 4334 submariners who lost their lives in both world wars, and to the 739 officers and men lost in peacetime submarine disasters.

Source; Campbell McMurray, Advisory Committee, March 2009.

Significance

A submarine to be operationally effective and technically capable has to embody certain key features: first, it has be built with a circular hull to withstand pressure underwater; second, it must have ballast tanks into which water can be readily admitted to take away positive buoyancy when she wants to dive, and from which the water can be readily expelled by compressed air at the end of the dive; and thirdly, to control the depth of the dive when the craft is submerged and under way, she must have horizontal rudders or diving planes and a propulsion system capable of operating without a supply of air, which until the advent of nuclear propulsion could only be provided by electrical power from batteries.

HOLLAND I is of the most profound historic importance for what she demonstrates of JP Holland’s skill as an innovative designer of early submarines, showing how he had successfully incorporated into his earliest designs these essential characteristics, such as horizontal planes, ballast tanks and petrol-engines driving into electrical motors, and certain other remarkable features, which overcame the serious deficiencies that had defeated earlier inventors.

As the Royal Navy’s first serious experiment in submarines, HOLLAND I by definition enjoys a unique significance. She represents the first faltering steps in what would be the immense and far-reaching revolution that such craft would effect as offensive weapons of war at sea. She was a sort of submersible torpedo boat, whose main asset was stealth. Submarines changed forever the character of sea warfare, whether as predators on sea-borne commerce or, as the capital warships of today, capable of mounting the most lethal and decisive attack on an enemy’s territory. Inevitably the prototype was quickly overtaken by newer, more technically advanced and capable submarines, such as the “D” class boats in 1908, the first true ocean going submarine, giving Britain a lead over the rest of the world which it took into World War One. By that date, some 400 such vessels were in service, distributed among the navies of 16 countries, those of the British and French accounting for some half of this total, and it all began with HOLLAND I.

The earliest submarine was a primitive craft, but an extraordinary creation nevertheless, whose character, living and operational environment was aptly summed up by the Navy’s first submarine commander, Lt FD Arnold Foster RN, when he observed in his diary, in 1902, that “the ingenious designer in New York evidently did not realise that the average naval officer has only two eyes and two hands: the little conning tower was simply plastered with wheels, levers and gauges with which some superman was to fire torpedoes, dive and steer and do everything else at the same time…”

Key dates

- 1900 Admiralty signs a compact with American Electric Boat Company to build five Holland submarines

- 1901 Vessel launched without fanfare

- 1902 In September, First Submarine Flotilla (two completed Holland craft), arrives in Portsmouth

-

1913

HOLLAND I lost off Eddystone whilst under tow to breaker's yard

- 1980 RN Submarine Museum initiates search for wreck with assistance from Royal Navy

-

1981

HMS BOSSINGTON reports possible contact - HOLLAND I later identified

- 1982 Vessel recovered from seabed, cleaned and treated with anti-corrosion chemicals

- 1984 Vessel placed on open air display

- 1993 Evident that chloride sponsored corrosion was causing acute deterioration of craft

- 1995 New thorough programme of advanced scientific conservation remedial treatment commenced

- 2001 Sequence completed - HOLLAND I placed on display in new, purpose-built, de-humidified gallery

-

2011

In 2011 Holland 1 along with the Royal Navy Submarine Museum formally became part of the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

Grants

-

1999/2000

The Heritage Lottery Fund awarded £699,200 to build a viewing gallery

-

1983

The National Heritage Memorial Fund awarded £19,000 for conversation work

-

1981

The National Heritage Memorial Fund awarded £10,000 for salvage works

Sources

Brouwer, Norman J, International Register of Historic Ships, Anthony Nelson, pp153-4, Edition 2, 1993

Holland 1, Royal Navy Submarine Museum

The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea Submarine, 1976

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, 1955

The papers of JP Holland pub, US Submarine Museum

Wilson AJW and JF Callo, Who's Who in Naval History from 1550 to the Present, 2004

Industrial Archaeology News Industrial Archaeology News Conservation of the Holland 1 Submarine, 2003

Navy News - Underwater aid for Navy's first submarine: Divers unlock Holland rescue, pp36, August 1997

The News (Portsmouth): Submarine museum goes worldwide, 26 May 1999

Compton-Hall, Richard, Warship World: No Occupation for a Gentleman? Submarining at the start, pp10-12, Winter 1991

Own this vessel?

If you are the owner of this vessel and would like to provide more details or updated information, please contact info@nationalhistoricships.org.uk